|

|

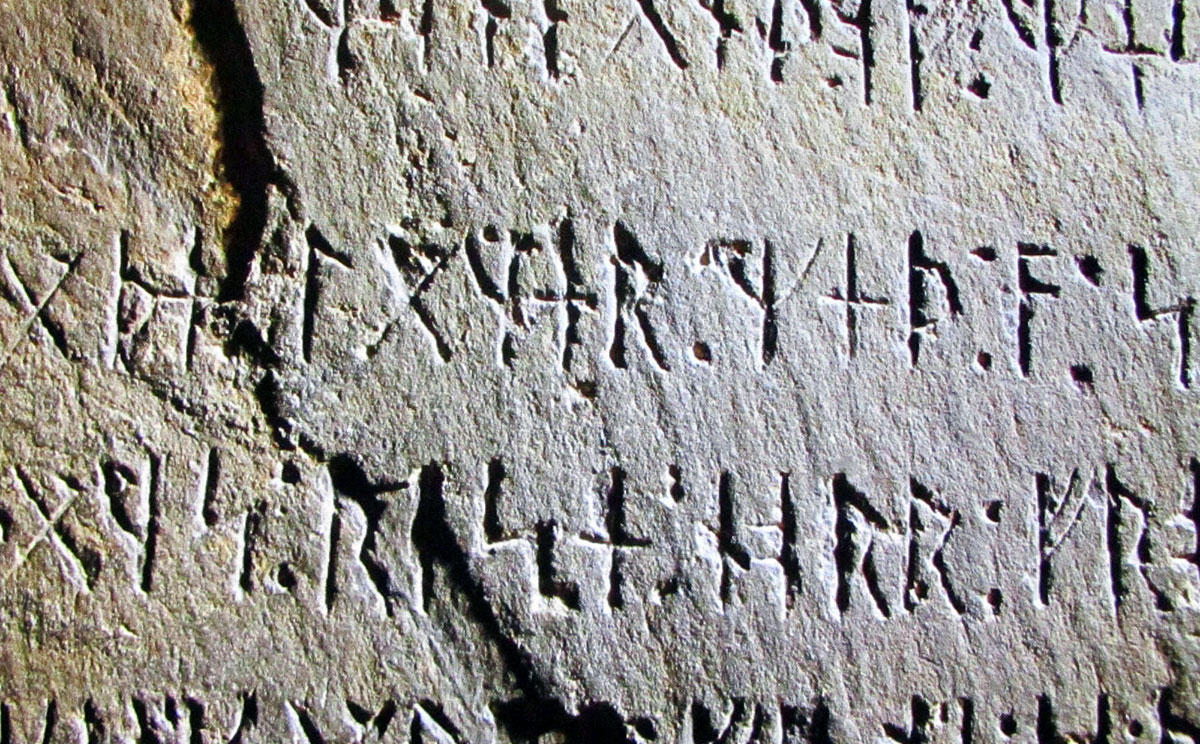

Decoding the Kensington RunestoneSkeptoid Podcast #934  by Brian Dunning Today we have for you a story about context. No historical event took place in a vacuum; and a thorough understanding of any such event requires an understanding of its context. What else was going on in the world at the time? What was happening 10 meters away, and 10 minutes before? This is the story of the Kensington Runestone, an apparent Viking artifact allegedly discovered in Minnesota in 1898. The only problem was its location: 3,000 kilometers inland from where any Viking was ever known to have been. Study of the runes inscribed on the stone lead us to one interpretation of its authenticity; the rest we get from its context: archaeological context of the find itself, and cultural context of the time in which it was produced. So let us now see to what conclusion those things will take us. To start with, we'll give an abbreviated history of Vikings in the New World. In 1960, archaeological evidence proved the existence of a Viking settlement on the tip of the Great Northern Peninsula of the island of Newfoundland in Canada, dated to the 11th century, a site now called L'Anse aux Meadows. It was occupied for only a short time, probably less than 10 years, and was likely a base camp for further exploration of the North American coast and not intended to become a permanent settlement. Likely reasons for its early abandonment include conflicts with North American indigenous people, and logistical problems with the climate and being so far away from established communities in Greenland and Iceland. So, fast forward some 850 years, to a field near the town of Kensington, Minnesota in 1898, where farmer Olof Ohman — a Swedish immigrant — was winching up tree stumps in a field he'd acquired to prepare it for plowing. Entangled in the roots of one stump was what appeared to be a large stone tablet covered in unfamiliar carved symbols. He shared it with people in the community, Swedish and Norwegian, including a newspaper and university professors. One of these was Olaus Breda, a professor of Scandinavian languages, who gave us the stone's first translation. It says:

Breda dismissed it as a hoax, based on the writing alone, which was full of inconsistencies. Over the years the writing has been critically examined by many experts, including direct examination in Scandinavia, and all find the same linguistic and orthographic flaws in it. Some of the words are wrong; they're modern and weren't found in Old Norse. For example, the word for discovery wasn't in Old Norse at all; it came into the language when it was borrowed from French in the 1500s. Some of the runes have umlauts, which were not used before the 17th century. The grammar and word endings didn't make sense for that time in history, and so on. Interestingly, some believers have regarded these errors as evidence pointing toward authenticity, on the principle that your average Norse explorer would have made spelling errors and so on just as the average person on the street would today. But would he have had the prescience to know words that wouldn't exist for another two centuries? Others have found further problems with the carving itself. The edges are sharp and do not show the weathering we'd expect with age. The runes are a cleaner, lighter color than the rest of the stone and with no patina, indicating that they hadn't been exposed or been buried for a long time. There are also problems with the story told on the stone. The stone's presumptive author couldn't have been on a journey from Vinland, as we have modern archaeological evidence that that region around Newfoundland was in Viking hands in the 11th century, not in 1362. Kensington was a lot more than 14 days travel from anyplace their ship could have been. Although in Ohman's day the Erie canal allowed ships to make it from the Atlantic to the Great Lakes, that didn't exist in 1362. They were a minimum of 1500 kilometers west of the farthest west they could have gotten in a longship. There is also a problem with Ohman's own story. He claims he studied the strange writing on the stone but did not recognize them to be runes, and figured it might have been an "Indian almanac." This doesn't add up, as Ohman owned a Swedish book titled The Well-Informed Schoolmaster which included a tutorial on runes. He'd signed his name and written the date inside the cover, eight years before the appearance of the runestone. Also, the text referencing the Virgin Mary is written as AVM, the same Latin script characters we use in English. The AVM is prominent and easily noticed. (If you thought it was suspicious that a Viking runestone would reference the Virgin Mary at all, this is one thing the carver got correct. AVM was used in Sweden as early as the 1300s.) So now we move on to context. Archaeological finds, like everything else, do not exist in a vacuum. There will always be context. After the stone was found, excavations were made all around the site. More thorough modern work was done in 1964, and even more thorough investigation over the wider area in 1981 — all searching for the archaelogical context of the runestone. In his book Encyclopedia of Dubious Archaeology, archaeologist Ken Feder writes:

Yet at L'Anse aux Meadows we have all of these things, plus much more. Context makes the difference between an actual artifact and a fake one. From an archaeological perspective, it simply isn't plausible that there would be no other record at all of this heavily manned journey of exploration that spent enough time in Kensington to carve the stone, and to have fought and died. Inevitably, the finding that the runestone is a modern forgery brings up the question of Olof Ohman, who would almost certainly have been the principal in the creation of the hoax, if not the actual hoaxer himself. What motivation would he have had? He did not try to get rich off the stone. He didn't seek out fame and fortune. He would have had no reason to do it, would he? And here is where our second point of context comes from. Not the archaeological context of the stone in the field, but the cultural context of a man producing evidence of early Norse visitation. What was happening in the local Scandinavian culture? In the 1890s, Vikings were very much in the pop consciousness — as were their voyages to America. This was a period known as the Viking Revival, which had seen a renewed interest in Vikings in Europe and by the late 1800s was spreading among Americans, particularly among Scandinavian Americans. This was largely due to the 1874 publication of America Not Discovered by Columbus by Norwegian-American Rasmus B. Anderson. By the 1880s, Scandinavian Americans were growing increasingly vocal about North America's Viking heritage. But a gauntlet was about to be thrown down. In 1893, Chicago hosted the World Fair. This particular edition was dubbed the World's Columbian Exposition, in recognition of the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus' arrival in the New World. This celebration of Columbus was seen as something of a challenge to the Scandinavian community in the United States, who had always believed that Vikings came here before Columbus. And although we now have the archaeological proof of this, in the 1890s that proof hadn't yet been discovered; the belief was largely based on stories from the sagas, which (many believe) cast North America as Vinland. Well, this notion of a World's Fair to celebrate Columbus as the first to sail to the New World was the final straw, and some Scandinavian Americans decided to do something about it. Two famed Norwegian shipbuilders, Christen Christensen and Ole Wegger, decided to prove that such a voyage was well within the abilities of Vikings even as far back as the 9th century. They constructed an exact replica of the Gokstad ship, an actual Viking longship discovered in a Norwegian burial mound in 1880. This is that very famous longship so dramatically displayed at the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo. They christened their replica the Viking. Viking was an open longship, 24 meters long and 5 meters wide. In April 1893, Captain Magnus Andersen set sail with a crew of 11 men from Kristiania, which is what Oslo was called at the time. They sailed a legit Viking longship through the North Sea, across the North Atlantic to Newfoundland, then to New York, then up the Hudson River and all the way to the Erie Canal, through the Great Lakes, and finally to Chicago, where the Viking was proudly displayed, a snub to the World's Columbian Exposition. To say that the local Scandinavian population was pleased would be an understatement. Only a few years earlier in 1887, baking powder magnate Eben Norton Horsford — an American enthusiast of Viking culture — commissioned a statue of Leif Erikson in Boston to commemorate the presumed Viking settlements in North America. A copy of this statue also went up that same year in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Two years later, Horsford had a stone tower erected in Weston, Massachusetts on what he believed had been the site of a Viking settlement called Norumbega. All these monuments are still there and can be visited. In 1923, some 25 years after the Kensington Runestone but during the same Viking Revival period, another runestone was "discovered" near Heavener, Oklahoma. It is universally considered a contemporary hoax. In the 1960s, two more were "found" in Oklahoma of equally dubious provenance. A few others have variously surfaced in other parts of the country since, all of them also fairly obvious hoaxes. And so it was during this period of "Viking mania," if you will, and widespread efforts to celebrate and prove the Vikings' pre-Columbian landings on North America, that farmer Olof Ohman — who just happened to be of Scandinavian descent — stumbled across this stone tablet in his field — which just happened to be covered in Viking runes. In orchestrating the hoax of the Kensington Runestone, Ohman was doing no more or less than were many others who shared his same heritage and admiration for their ancestors, and hoped only to see them recognized. And thus we conclude our little story about context. Neither malice nor greed were required to bring the runestone to life and to make it a part of pop culture. You can visit the actual stone, it's on display at the Runestone Museum in Alexandria, Minnesota. If you do, regard it not as a deceit, but as a symbol of pride; pride in one of history's greatest and most impactful cultures, the Vikings.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |