|

|

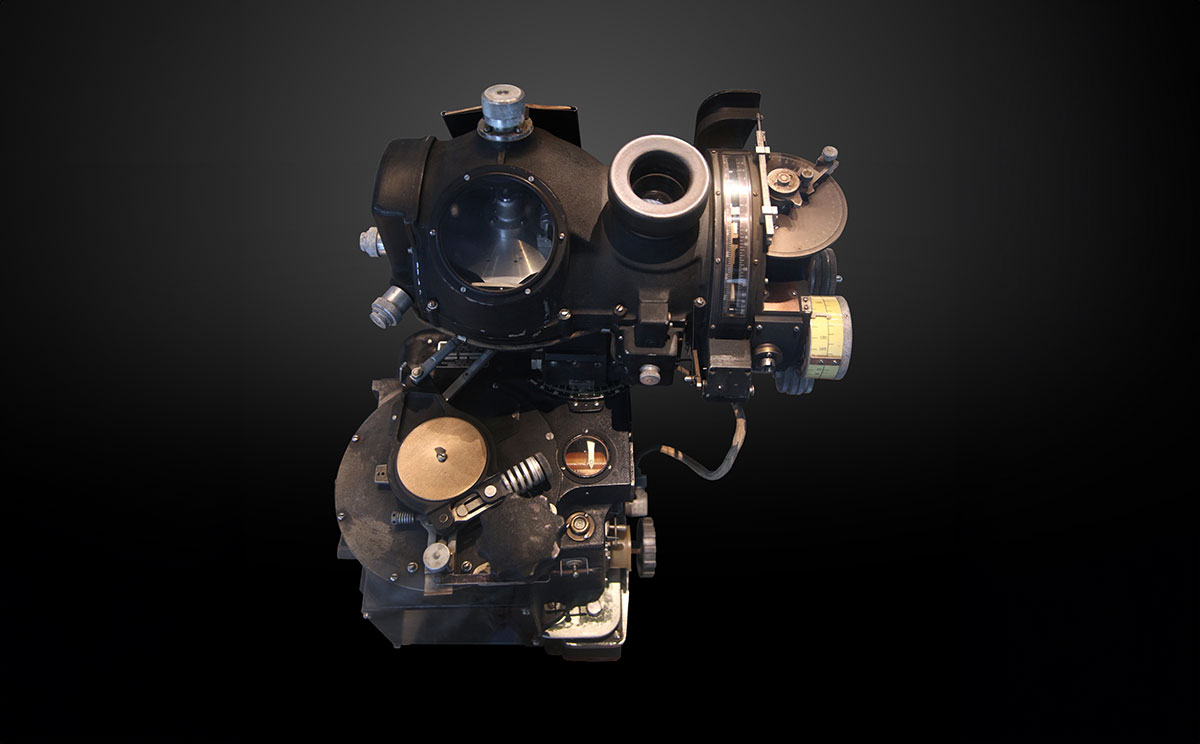

The Secret of the Norden BombsightSkeptoid Podcast #897  by Brian Dunning Ah, the famous Norden bombsight. We gasp whenever we see one in the World War II wing of an aerospace museum. We read the placard telling us that it was so accurate it had to be highly classified — and then we go home and see something about it on the Internet, and we're told the exact opposite: that it was actually so bad that the real reason it was classified was so the Germans wouldn't find out how terrible our capabilities are. Which story is true — if either one is? Granted not everyone knows about the Norden bombsight, and a lot of you have probably never heard of it before. It was supposed to be this incredibly accurate bombsight that won World War II for the Allies, allowing our high-altitude B-17s to destroy the Nazi factories with unprecedented precision. But for those of you who have heard of it, the thing you probably think you know is that the Norden bombsight was actually terribly inaccurate. Like, missing its targets by half a kilometer. That's the dirty little secret about this famous secret weapon — that it was virtually useless. You may have seen this revealed on any number of History Channel shows. You may have heard Malcolm Gladwell reveal it in his TED talk, and YouTube is bursting at the seams with generic conspiracy videos making the same claim. Whole books have been written showing that the Norden was worthless, and that that was the secret Allied intelligence had to protect. Well, guess what? That's all pop culture misinformation. It's sizzle and it sells, and so it's the version you'll probably continue to hear in most any programming on the topic. But not here on Skeptoid, where our job is to separate fact from fiction, to tease out misinformation from pop culture. So sit back, enjoy, and let Skeptoid pull back the curtains. So the basic problem of high altitude bombing is a pretty obvious one. You're in a certain plane, flying a certain speed, at a certain altitude, with certain wind conditions, dropping bombs that are certain sizes and shapes and weights, and you need a formula that can combine all of these variables and tell you exactly where the plane needs to be and exactly when to drop the bombs. We'd learned enough during World War I to know that this was a problem we really needed to figure out. World War II was to be a war of industry, and bombing the enemy's industry was a primary strategy. Carl Norden was a Dutch-Swiss immigrant who consulted for the US military on gyroscopically stabilized systems, and was brought in in 1923 to find a way to stabilize the current bombsights. From then on, the Norden company was the military's go-to provider for this all-important task — to the point that $1.1 billion was spent developing it. As American engineers worked on new bombsights, German engineers did the same. Both knew the problems very well, and both knew the same basic way to solve them: gyroscopically stabilized bombsights communicating with gyroscopically stabilized autopilot systems for the aircraft. The goal for both sides was to develop a bombsight which the bombardier could calibrate, then enter in all of these variables, then spot the bombing target in a telescopic sight; and if all went well, the plane would stay on target, close in, and automatically release the bombs at exactly the right time and place. The Norden bombsight is often described as the first bombsight that put all these pieces together and worked successfully, but that's not really fair. Norden was one company in the United States developing such systems through the 1930s; but Sperry was also doing the same. And in Germany, the Carl Zeiss company — yes, the same Carl Zeiss that makes your camera lens — was also building similar systems. And really, none of these companies were working in isolation. In the United States, the government ordered Sperry and Norden to work together to build their bombsights to work with the Honeywell autopilot systems. This is an oversimplification of what was a decade-long arms race between these competing companies, but it's how the situation ultimately worked out. Plenty of German engineers worked at all three companies, and at least one of them, a Herman Lang at Norden, gave the blueprints of the Norden devices to the German military in 1938 — and was then promptly arrested for espionage once he returned to the United States, but the plans had been delivered. So the Germans, with full knowledge of the Norden bombsight and a working prototype based on the plans provided by Lang, still proceeded with their own existing device, finding nothing in the Norden they hadn't already figured out on their own. Lots of smart people, all working on the same problem which was well understood, had all come up with basically the same solution. The Norden Mk. XV, the Sperry S-1, and the Zeiss Lotfernrohr 7 bombsights all had the same basic configuration. They were what we call tachometric bombsights, built on gyroscopically stabilized chassis mounted on gimbals inside the aircraft, so that as the aircraft moved around, the bombardier could maintain a perfect sighting on the target. Atop that base was the telescopic sight and the controls for adjusting everything. Where the Norden differed from the other two was in its complexity, which was really a curse in more ways than an advantage. First of all, while the other two were single self-contained units, the Norden was in two parts: the lower gyroscope which remained mounted in the aircraft, and the upper sighting assembly which was securely removed from the aircraft when not in use. The DC motors driving its gyroscopes threw a lot of carbon dust from the brushes, which got into the bearings and required regular cleaning and maintenance. It had 61 ball bearings which required lubrication and cleaning. Operation of the Norden was also more difficult than with the other two. The first step of the bomb run was to right the unit to get it perfectly level, a process requiring the use of finicky spirit levels that required 8 minutes and 30 seconds to complete, which is a chunk of time out of a bomb run. Then, many settings had to be entered into the device based on the speed, altitude, the trail (how much farther behind the aircraft would the bombs hit the ground based on their aerodynamic qualities), weather conditions, and more — all using dials located only on the right side of the unit, while Sperry and Zeiss bombardiers could use both hands. Finally the bombardier would locate the target and work with the pilot to get the plane onto the planned approach, before connecting the bombsight electronically to the aircraft's autopilot to stay precisely on the final bombing run. There was a lot working against all three bombsights. First of all, planes move around a lot, they bounce and vibrate, particularly when they're in combat and potentially flying through flak or dodging it. At the instant the bombs release, no plane would ever be exactly level, and every plane would always impart some unwanted movement to the bombs. Pilots never wanted to make the bomb run at a level altitude, as changing altitude was a crucial maneuver to defeat the flak gunners. Falling bombs would pass first through massive turbulence caused by the bomber fleet, and then through differing zones of wind. Weather often cooperated and often did not, and since everything depended upon visual sighting of the target, frequently the whole operation was based on bombardiers' best guesses. Air temperature and humidity were also variables taken into account by the tables used by the bombardiers, but the actual conditions rarely exactly matched the predicted or assumed conditions. The number of inherent problems that were outside the control of the bombsight went on and on. So the stories you might hear about how the Norden performed well in testing and controlled demonstrations, but widely missed its targets during actual combat are true — but that's true for all bombsights. There's only so much dropping the bomb at the right time and place can do; so much influences everything that happens next. But so far as what the bombsights could do, they did it very well. The Norden did as good a job as was possible, as did the Sperry and Zeiss units. In fact, none of these designs has ever been substantially improved upon, in all the decades since; only incremental improvements such as better electronic servos and controls. In fact the Norden continued to be used as the United States' primary bombsight through the Vietnam War, until they were finally replaced by new generation systems such as the radar-guided Sperry-Rand K-3A bombing navigation system. These newer systems were better integrated into modern aircraft and made the bombardier's job easier, but in point of fact, could not release their bombs any more accurately than did the Norden — again, because the real problems are outside of the bombsight's control. These problems remain today, and are why we now use guided munitions that correct their own course as they fall. The Norden bombsight truly was as good as a bombsight could be, and the modern stories you hear that it was actually terrible are false. So why is it the Norden that's said to be the best bombsight, and not the Sperry? Why did the Sperry, with its simpler design, better electronic servos and ease of use, not become the United States' primary bombsight? Turns out this had to do with other factors. First, Sperry had already been an international company prior to World War II, with facilities in both Japan and Germany. This was considered a security risk. Second, two of Sperry's key personnel — their military marketing representative Fred Vose and their main advocate in the military, Major General Frank Andrews, were both killed early in the war. Third, Norden really played up the classified nature of their device, emphasizing its theatrical secure removal from planes between uses, and working all this for its marketing value; while Sperry never even acknowledged that they made bombsights. Finally, Norden, with its original 1923 contract, simply had the inside track. And so, seek not to place blame where it is undue, simply for sizzle and clicks. Top engineers in their field actually do tend to know what they're doing, as a general rule; even if the job they're tasked with is a nearly impossible one. The Norden bombsight was as good as it reasonably could have been, no matter what TED talks and YouTube have to sell you.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |