|

|

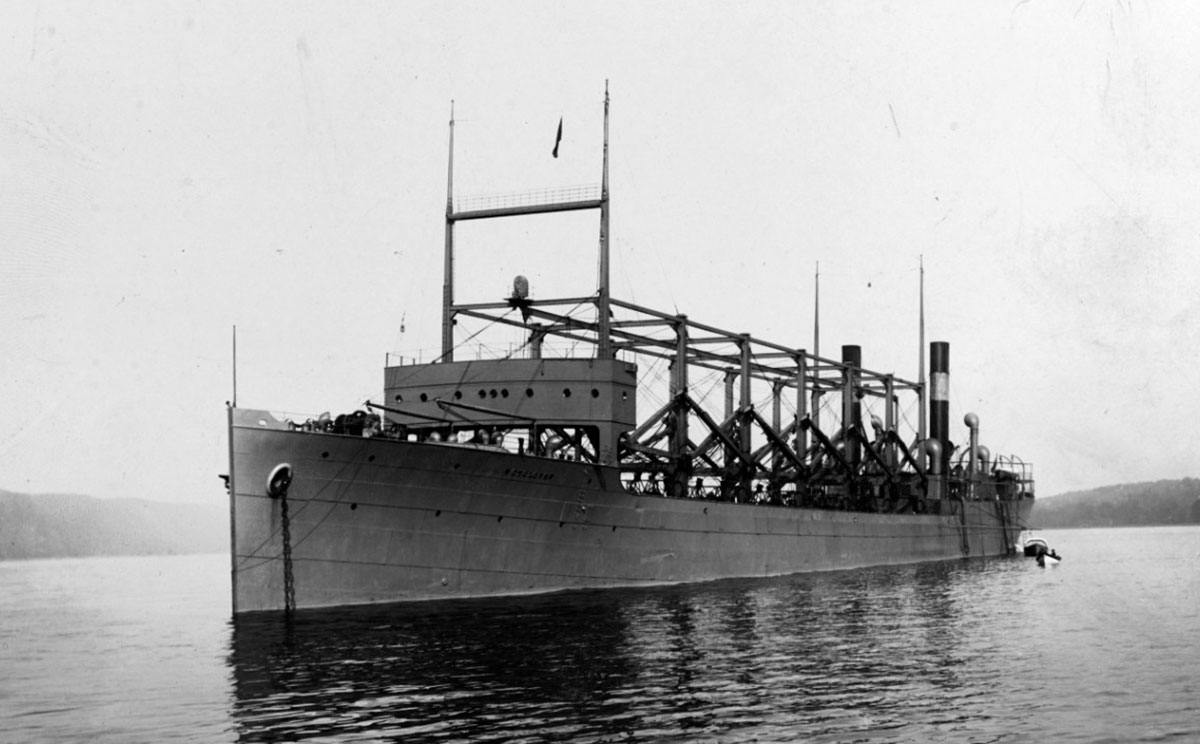

Finding the USS CyclopsThis most famous ship disappearance from the Bermuda Triangle probably had nothing to do with it. Skeptoid Podcast #758  by Brian Dunning It was March of 1918, and naval warfare in the Atlantic theater was in full swing. Although the Americans had only been in the war for a little less than a year, their role in resupplying the Allies by ship across the Atlantic was a crucial one. And supplying those supply ships were the equally crucial colliers, like the USS Cyclops (AC-4), which brought tons of coal to a thirsty fleet every day. But this time, the massive bulk carrier was doing an odd job: transporting a load of manganese ore from Brazil to Baltimore, for use in the manufacture of munitions. It was a route that passed inevitably through the heart of the Bermuda Triangle. And when Cyclops disappeared completely somewhere along that 5,000 km journey, it passed out of the realm of naval lore and into the annals of the paranormal. Today we're going to study the disappearance of the Bermuda Triangle's most famous victim. She was a monster: 165 meters long with a displacement of 19,360 long tons (the unit used for warships). Her normal complement was 236 officers and crew, but on this voyage she had additional passengers for a total of 309 (often variously misreported as 293 or 306). Her massive compartments had a capacity of 8,000 long tons of coal, more than enough to completely fill three average battleships of the day. Her most prominent feature visually were the seven coaling towers bristling with booms, derricks, spars, and cranes for getting the coal on and off fast. When she was built, she was the second of four sister ships, the Proteus-class of US Navy colliers that included the Proteus (AC-9), the Nereus (AC-10), and the Jupiter (AC-3). Although the disappearance of Cyclops is nearly always described as the US Navy's worst loss of life not directly related to combat, let's set the tone for today's episode by establishing that's not even close to true. In 1800, the frigate USS Insurgente sank in a hurricane with the loss of 340 lives, and in 1944, 31 vessels of Task Force 38 were sunk or damaged in Typhoon Cobra with 790 lives lost. Complicating our journey of discovery is that there is no official report on the loss of Cyclops to which we can turn. The Navy never opened an investigation into it. This is not because of some dark conspiracy, but simply due to the fact that World War I was at full bore and ships were being lost all the time. Resources were simply not available to fully investigate every sinking, and it simply wasn't a priority. The facts that we do have are on the slim side. Cyclops left Salvador, Brazil on February 22, 1918 for a direct cruise to Baltimore — though some sources say Norfolk, it doesn't really matter as the destination was the inlet to Chesapeake Bay either way. The load was an unfamiliar one she'd never carried before: manganese ore instead of coal. Manganese is heavier and denser than coal, and filling the holds ended up being a load of 10,800 long tons — more than 25% over the ship's capacity. But if that wasn't enough of a bad start, it was found that one of the two engines had a cracked cylinder and could not be used. So Cyclops left port dangerously overloaded and underpowered. Underway it was discovered that the ship was riding below the Plimsoll line, a hashmark painted on the hull amidships showing its maximum safe depth. So as a precaution, Cyclops made an unscheduled stop at Barbados for inspections. No leaks or other problems were found, so they set off again on the final leg on March 4. At that point, they were probably about a week out from Baltimore, but we don't quite know for sure because of the reduced speed due to running on only one engine. Regardless, the ship was never again seen or heard from: not a single radio call was made, and no piece of debris or other evidence was ever found. There were one or two anecdotal reports or sightings from other ships, but none ever stood up to scrutiny. The fact is Cyclops was lost, and nobody has ever had any clue what happened. But there are, of course, plenty of reasonable possibilities. But we can first address the popular unreasonable possibility: that Cyclops was a victim of the Bermuda Triangle. The Bermuda TriangleCyclops was one of the original cases presented when the Bermuda Triangle mythology was first publicized by author Charles Berlitz in his 1974 book The Bermuda Triangle. He devoted only two pages to it and his account was mostly prosaic and devoid of his usual sensationalism. But he did imply that the ship was lost in the Bermuda Triangle (improbable, since the Triangle only encompassed a small part of Cyclops' route), and that none of the proposed Earthly explanations were sufficient to account for its sinking. He also asserted there were no storms along the route... something we'll come back to later. We do have a full episode on the Bermuda Triangle (episode #337 if you want to check it out) but the short version is that data show that the region is no more dangerous than any other on the planet. Planes and ships do not disappear there at a higher rate than anywhere else, and there is neither evidence nor reason to suspect any unexplainable perils there. That's about all there is to say on the Bermuda Triangle theory; so let's move on to some more likely causes. Sunk by a German SubIt has been proposed that Cyclops could have fallen victim to a German submarine. This is a perfectly plausible theory. Germany was in a period of unrestricted submarine warfare; Cyclops was a perfectly valid and particularly juicy target; and German subs had sunk many Allied ships all along much of that route. German sub captains were not in the habit of being modest about their kill records, and no record has ever been found of a captain making a claim for Cyclops — a piece of evidence which would be easy to find in the records of the German navy, and which would almost certainly exist if that's what had happened. Betrayed by the CaptainMuch has been written about the character of Cyclops' captain, Commander George Worley. He was German born, having changed his name from Wichmann; and one of Cyclops' passengers, the American Consul General at Rio de Janeiro, was openly pro-German. Thus, some conspiracy theorists have hypothesized that perhaps the two men conspired to somehow turn Cyclops over to the Germans instead of delivering her cargo to Baltimore. While it might make a good movie plot, it's highly implausible — why would an entire US Navy crew go along with that? — and purely speculative with not a shred of evidence to support it. A Mutinous CrewBy all accounts, Worley was also both a tyrannical bully and a weirdo prone to making very poor command decisions. Based on this alone, some have speculated that the crew may have mutinied. Successful mutinies don't typical rely on a strategy of the sailors choosing to scuttle their own ship from underneath themselves, so they'd have had to go somewhere first. A 165-meter ship is somewhat easy to see, and it never was. (Note that anecdotes do exist of Cyclops being spotted here or there in the weeks following her disappearance — basically, nautical Elvis sightings — but none of these were either credible or corroborated.) Structural Failure in a StormAbout a year after Charles Berlitz published his book promoting the Bermuda Triangle as a real mystery, skeptical researcher Larry Kusche published The Bermuda Triangle Mystery - Solved which expertly debunked pretty much all of the false mythology; and he devoted a chapter to Cyclops. Kusche calculated that Cyclops' reduced speed of about 10 knots would have brought her to the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay about 6 days out from Bermuda, on March 10. Rather than accepting Berlitz's assertion that the weather had been calm, Kusche obtained the weather records for that day from the National Climatic Center. Sure enough, gale warnings had covered the whole of the east coast. Cyclops would had have hit winds ranging from 40 to 60 knots. Kusche also found reports that Captain Worley had once told a Navy Lt. Commander that he always kept the cargo tanks opened at the top (though this would have been unusual and it's possible Worley was pulling the guy's leg), and that a sailor from her penultimate voyage reported to the captain that the ship was visibly bending with the contour of the waves, causing pipes to contact surfaces they were suspended away from. Combine the storm with the facts that Cyclops was dangerously overloaded and her ability to maneuver was crippled by having only one engine working, Kusche was satisfied that a probable cause for the loss of Cyclops had finally been established. A ship that size simply cannot rest its stem and stern on the peaks of successive storm swells, and not break in half from the weight of its grossly overloaded center section. A footnote to this is that Cyclops' sister ships, Proteus and Nereus, survived into World War II when both were lost at sea while fully loaded and in bad weather. Also like Cyclops, both were presumed to have been sunk by German subs, but again, no German sub captains made claims for either ship. This mystery is only likely to ever be solved if and when the wreck of Cyclops is ever found. There is a chance that it might be. In 1968, the minesweeper USS Exploit (AM-440) was involved in the search for the missing submarine USS Scorpion (SSN-589). It was about 40 nautical miles northeast of Cape Charles, near enough where Cyclops might have entered Chesapeake Bay. Master diver Dean Hawes descended onto a wreck but it wasn't the sub; it was a great giant ship covered with towering gantry cranes, unlike anything he'd seen before. Bad weather forced them to cut this dive short and the wreck was marked with a buoy. Later, shown a picture of Cyclops, Hawes was sure it was the very ship he'd examined. Scorpion was soon found elsewhere and there was no longer any reason to return to the marked site. However, years later, Hawes and a Virginia Congressman persuaded the Navy to try and rediscover it, which was turned into a dive exercise. Although the original buoy was long gone, a ship was found; but unfortunately, Hawes — watching on a TV monitor — saw right away that it was nothing like the first one he'd seen. So, potentially, who knows... perhaps this episode will have a major update one day. It should be noted that the location of Hawes' wreck — possibly Cyclops — is nowhere remotely near the Bermuda Triangle.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |