|

|

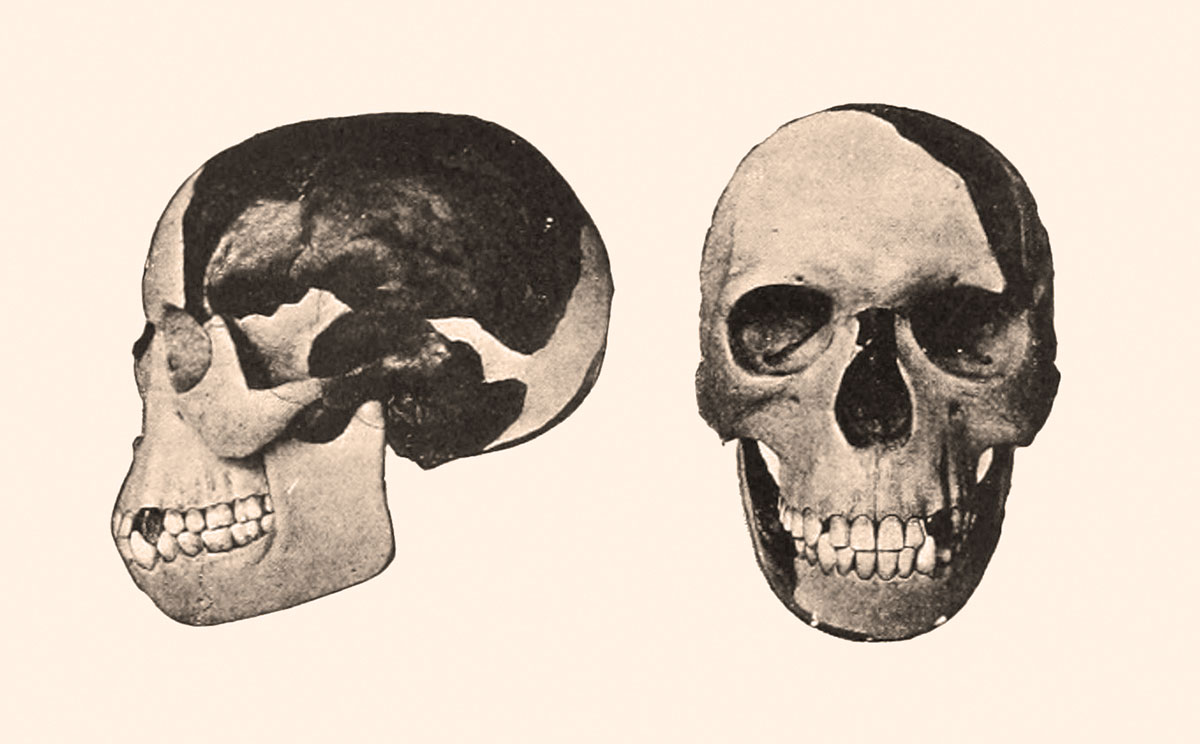

10 Great Science HoaxesA look at those few times when hoaxers came closest to fooling those who knew better. Skeptoid Podcast #617  by Brian Dunning Let's pull back the curtain on some of history's biggest science hoaxes: cases where someone thought they could pull the wool over the eyes of people who know better than they do. Today's subject is hoaxes launched upon scientists. To be included in this episode, these hoaxes had to satisfy two basic criteria. First, they had to be deliberately hoaxed by people who were being consciously deceptive. Second, they had to be scientific hoaxes; in other words, designed to fool scientists, not just the general public or investors. This wouldn't include the legendary stone tablet allegedly found in the Oak Island Money Pit, for example, because the miners who made that tablet did it to fool investors into giving them more money to continue digging. Such was the case with countless gold and silver mines as well. Today we're going to look at those daring few who had the gall to think they were going to fool the real experts. Let's dive right in. 1. Subliminal AdvertisingIt was the hoax that launched an entire cottage industry. At a movie theater in New Jersey, researcher James Vicary set up a projector to flash the words Drink Coca-Cola and Hungry? Eat Popcorn onto the screen throughout the show, so fast that nobody perceived them, but the messages got through nevertheless. Sales of the two products shot up by 18% and 58% respectively. The only problem? It never happened. Vicary made the whole thing up. He revealed that the experiment never took place in a magazine interview in 1962 as his claim had begun to fall apart. But pop culture had already taken a firm grip on its belief in subliminal advertising. Twelve years after Vicary's admission, Wilson Bryan Key's famous book Subliminal Seduction cited the nonexistent experiment as a foundational proof of the effectiveness of subliminal advertising, now known to be worthless. This whole case was discussed in detail in Skeptoid #63. 2. The Sokal PaperScientists were again fooled in 1996, when a new trend in deliberate hoaxing was launched into prominence. Physicist Alan Sokal was tired of relaxed standards in some scientific journals, especially those in the humanities; so he thought he'd send them a wakeup call. He selected the journal Social Text, a progressive humanities journal published by Duke University, and wrote a paper which was pure, unadulterated nonsense from beginning to end. Its title was "Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity" and it argued that quantum gravity has a liberal bias. The reviewers published it without understanding a word of it — and probably without even trying to understand it. The reaction from the community was legend. Ever since, authors have been trying to hoax journals with papers of deliberately low standards, and good journals have been forced to step up their reviewing game in response. This so-called white hat journal hoaxing was the subject of its own Skeptoid episode, #543, which is fat and juicy with many more such examples. 3. Vaccines & AutismWhile Sokal had good intentions and caused good things to happen, Andrew Wakefield did neither. In 1998, he wrote a fake research paper claiming to prove that the MMR vaccine caused autism, falsifying all of the research and data. As he had legitimate standing in the medical community at the time, his paper was published in The Lancet, a top medical journal. This paper was "case zero" for today's widespread belief that vaccines cause autism. The result is that diseases like whooping cough and measles, previously virtually eradicated by vaccines, have come stampeding back, and many children die each year as a result. This arguably makes Wakefield the world's public enemy #1. Fortunately the deceit did not withstand scientific scrutiny forever. The article was retracted, and Wakefield was found guilty of three dozen charges by the British General Medical Council and stripped of his medical license. Unfortunately, all that took twelve years, more than enough time for his disinformation to take solid root in pop culture. 4. ArchaeoraptorIn 1998, the fossil of a prehistoric bird was illegally smuggled out of China. It was imprinted in a flat slab of slate, shattered and glued back together. The slab was purchased by a museum in Utah, which then called paleontologist Phil Currie and the National Geographic Society. As Currie and his associates studied it, problems began to emerge, and it became clear that it was a composite of three to five different fossils. The journals Nature and Science both rejected the team's paper on this basis, but National Geographic — a consumer publication with no peer review — went ahead and published it anyway. They even assigned this nonexistent bird a scientific name, Archaeoraptor, and called it a missing link between dinosaurs and birds — to much well-deserved criticism. Fortunately, by 2001, both Nature and National Geographic had published complete explanations of how the process went wrong. 5. The Disappearing Blond GeneIn this case we have no "case zero" — the origin of the rumor seems to have been lost to history. But every few years, someone somewhere runs an article claiming that the gene for blond hair, which is a recessive allele, will soon disappear from the human population. It is genetically nonsensical: the prevalence of recessive genes remains stable in large populations; but to the average person on the street, it sounds logical. This perennial story surfaced again in 2002, with the added specifics of being the result of a study by the World Health Organization, and that the last blond person would be born in Sweden in the year 2202. The story was picked up my major news outlets worldwide. Snopes did an impressive piece of investigative journalism that failed to find the 2002 origin, but did find repeated iterations of this story going all the way back to 1865. 6. Piltdown ManAnother fossil composite fooled scientists, this one in 1912, by career archaeological hoaxer Charles Dawson, known for quite a few falsified discoveries. He took a modern human skull and fitted it to the jaw from a modern orangutan, staining them both to look old and match, and made other manipulations to them. He then pretended to "find" the skull at a dig at Piltdown, Sussex, along with other fossils. Interestingly, Piltdown Man has a modern footnote. In 2016, an interdisciplinary team sought to prove who created the hoax, and gave us the conclusion we have today, that it was almost certainly Dawson, working alone. Genetic tests on the Piltdown Man pieces prove that they come from the same originals that Dawson used to piece together other hoaxes. For example, he also produced fossils from a different site he called Piltdown II, and these included teeth from the very same unfortunate orangutan. 7. The Cardiff GiantThis famous petrified man was built not to hoax mainstream scientists, but as a genuine attempt to fool creationists. In the 1860s, tobacco farmer George Hull was exasperated by debates with Biblical literalists who believed that giants had once walked the Earth, so he conceived to make the creationists look foolish by making a petrified giant realistic enough that they would take it as the real thing, and then he would expose the hoax. It was created with great care, and Hull had it discovered during a mock well dig on his cousin's farm in Cardiff, New York, an area popular with revival meetings and hellfire preaching, and was even near where Joseph Smith founded Mormonism. Things didn't go quite the way Hull planned, however. Although the giant made quite a splash in the news, actual scientists immediately pointed out that it was a carved hoax. Hull got only a fraction of the satisfaction he hoped as only a few creationists defended the sculpture as a real fossilized giant. In time, it was sold off to the carnival circuit as a sideshow attraction. 8. The Tasaday TribeIn 1971, the existence of a remote primitive tribe in the Philippines was announced: the Tasaday, presented as having never had any contact with the outside world. But after years of inconsistencies discovered by anthropologists, and things like TV crews catching them wearing Western clothes when the cameras were off, they were dismissed as a hoax, perpetrated by Manuel Elizalde, a government official. The truth, as discussed in depth in Skeptoid #490, was far more nuanced. The most likely explanation for the Tasaday is that they had indeed been separated from society, probably fleeing into the forest to hide from slavers in the 1800s. There they remained, having limited contact with outsiders, and they did become somewhat culturally distinct. But Elizalde probably did exaggerate their primitivity for the cameras, which Western audiences consumed voraciously. 9. The Mechanical TurkThis next one was a fascinating case of a deliberate hoax created against the hoaxer's own will. In 1770, Werner von Kempelen was a great scientist and engineer in the court of Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria. After a show by a visiting magician, she challenged Kempelen to use scientific ingenuity to devise a trick more mystifying than anything the magician could do. The result was the Turk, a chess-playing automaton that appeared to be mechanical, but actually concealed an expert chess player. What began as a lark turned into his full-time job for years, as he was obliged to tour the world showing off his creation at Maria Theresa's command, and even having to represent it to his peers in the sciences as a genuine mechanical device. Although Kempelen regretted every minute of it, his Turk defeated chess players and heads of state worldwide for 80 years, including Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin. 10. The Kensington RunestoneIn 1898, Minnesota farmer Olof Ohman, part of the large Swedish immigrant community, reported finding a great 92-kg block of stone under a tree near the town of Kensington as he was clearing a field, inscribed with ancient Norse runes telling the story of adventuring Vikings. The overwhelming majority of Scandinavian scholars were able to easily dismiss it as a hoax from a combination of lexical, grammatical, and paleographic evidence. For example, the stone used 14th-century runes, but used modern grammar that did not exist in the 14th century — to say nothing of the fact that no remotely accurate interpretation of history put Vikings in Minnesota before it was settled by Europeans. However, a core of mavericks — mostly non-experts — has always upheld the stone as genuine. Local rumors held Ohman himself to be the original hoaxer, likely in concert with some of his Swedish cohorts. As we can see from these examples, hoaxes that cause a significant disruption to science are pretty few and far between. It's easy to hoax non-experts, but fooling the people who know a field better than you do is always going to be harder, which is why we just don't see it happening — really ever, maybe for a very short time, or maybe fooling only a small number of people. These were among the biggest scientific hoaxes I could find, but even among those I didn't include, the real experts in a field simply can't be fooled for very long. So whenever you hear that some science is just a great big hoax, you have very good reason to be skeptical.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |