|

|

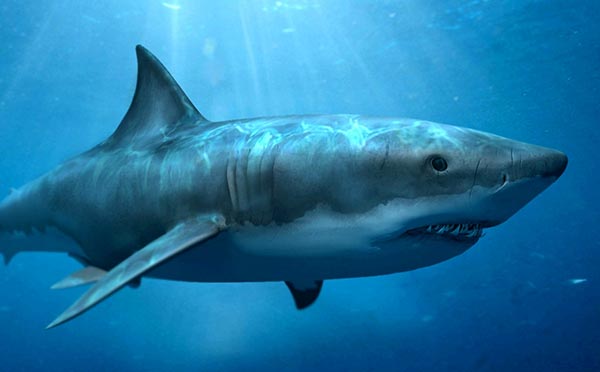

Megalodon MythsThe Discovery Channel wants you to think that a giant prehistoric shark may still swim our oceans. Skeptoid Podcast #445  by Ryan Haupt Sharks are a group of Elasmobranch Chondrichthyian fish that first evolved some 420,000,000 years ago and today contains over 470 species which tend to be represented by a single image: a sleek mindless killing machine. This images is often typified by the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), the 20 foot predator capable of swimming at 35 miles per hour and responsible for the largest number of fatal attacks on humans. And while the great white shark is indeed the world's largest extant (meaning not extinct) predatory fish, our fossil record tells us that in the past there was an even more monstrous beast lurking in the depths: Carcharocles megalodon, often referred to by just its species name Megalodon, meaning large tooth. In 2013, The Discovery Channel's Shark Week released a fictional documentary called Megalodon: The Monster Shark Lives, which purported to present evidence of the continued existence of the prehistoric animal. Was the evidence they presented an accurate representation of the current scientific consensus, or can we say with all reasonable certainty that the oceans are no longer inhabited by this awesome creature? Accounts of giant triangular fossil teeth date back to the Renaissance, where they were identified as glossopetrae, or petrified tongues of dragons or snakes. It took Danish naturalist Nicolaus Steno to recognize that these were in fact the shark teeth, which he drew along with a reconstruction of the head in his 1667 book The Head of the Shark Dissected. However, no name was ascribed to the fossil until 1835 in Recherches sur les poissons fossiles (Research on fossil fish, published in 1843) by Louis Agassiz when he dubbed it Carcharodon megalodon, placing it in the same genus as the great white shark. Since then, the taxonomy of this animal has been heavily debated, with many modern researchers arguing that the animal actually belongs in not just a different genus but a different family. They have moved the shark from family Lamnidae (which contains the great white shark) to family Otodontidae with the new genus Carcharocles but the same species name megalodon. To avoid confusion for the rest of piece I will refer to the animal a C. megalodon, except when talking about the documentary where they only use the species appellation Megalodon. C. megalodon teeth are indeed the largest shark teeth ever found, with some measuring just over 7 inches long. The teeth are roughly triangular in shape with small serrations around the edge and look very much like a scaled-up modern great white tooth. Whale vertebra from the same time period have been found with gouge marks that potentially match C. megalodon teeth suggesting that this animal filled the same niche that orca fill today: a whale hunter. Estimating the size of C. megalodon is difficult and contentious, because the majority of the fossils found are isolated teeth or disarticulated vertebra. Several different methods have been attempted to estimate the length and body mass of the animal. Paleontologists are people too, and there's glamor to be had in finding the "biggest" of any given group, but most reasonable estimates place the length of the shark between 52 and 67 feet weighing in somewhere between 48 and 103 metric tons. Bite force estimates using the more conservative minimum and maximum estimates for body mass were calculated to be between 108,514 Newtons (N) and 182,201 N, an order of magnitude above the largest bit force for a great white shark at 18,216 N. C. megalodon had a cosmopolitan distribution with fossils being found in Europe, Africa, North, South, and Central America, Australia and other islands around Oceania, Japan, India, and several islands in the Caribbean. These localities represent a variety of near-shore environments but it is thought that the lifestyle of C. megalodon included time spent far off-shore too, as seen in modern-day great white sharks. The oceans were generally warmer during the time C. megalodon lived, and cooled with the closure of the Isthmus of Panama roughly 1 to 2 million years before the shark went extinct. To summarize, based on the evidence available, paleontologists conclude that C. megalodon was a large predatory coastal shark that went extinct 2.6 million years ago. We'll go back to the evidence for its extinction after reviewing what the Discovery Channel presented on the matter, but first how is this animal actually represented in the fossil record? In the fossil record, not all things preserve equally. Taphonomy, which is the study of everything that happens after the death of an organism up until it's discovery by humans, has classified a number of different filters that affect what we eventually find in the fossil record. Understanding these filters can help us better make sense of some of the more outlandish claims of C. megalodon's continued existence. Like all sharks, C. megalodon would have had a cartilaginous skeleton, instead of the calcified bony skeletons found in the majority of animals we would think of as fish, like tuna or salmon. Cartilage is softer and less mineralized than bone, thus less likely to preserve in the fossil record, meaning that the majority of shark fossils are known from their much harder teeth and vertebral discs. Sharks produce and shed a staggering number of teeth; up to 35,000 teeth in a lifetime for some groups. The sheer number of teeth is itself bias in the fossil record: the more common something is, the more likely we are to find it. Size also exerts a similar bias. A large tooth is more likely to be seen, noticed, and collected than a small tooth. The distribution of an organism matters too. The more places something lived, the more odds there are of it being preserved. Since we established the C. megalodon was a very extensive shark, this increases the chances for preservation. The final relevant bias is the difference between oceanic and continental depositional environments. As might be expected, it is extremely difficult to collect fossils from the deep ocean; whereas near-shore environments that are tectonically uplifted or exposed with dropping sea-levels have a much better chance of being prospected by paleontologists. The fact that this shark spent at least part of its life-cycle near the coast gives us much better odds of finding its remains. With all that in mind, lets take a look at what the Discovery Channel had to say about the prospect of this shark still lurking in the deep dark seas. First aired in 2013 with a follow up in 2014 Discovery Channel's Megalodon: The Monster Shark Lives now ranks as the most viewed Shark Week episode to date with 4,800,000 viewers. The docufiction is set in South Africa in April, 2013, and begins with a sport fisherman fighting for two hours to reel in a big fish, eventually breaking his line. The boat is then attacked, the camera is dropped, and we cut to a news report about the events we just saw. The officials say it was a whale breaching, but the wreckage doesn't support being hit from above, so they bring in expert marine biologist Colin Drake (portrayed by South African actor Darron Meyer according to his own Internet Movie Database page) to crack the case. Colin feels it's his mission to find the deadly predator lurking in these waters so he can prevent it from killing again. They introduce viewers to a supposed 30 foot great white shark named Submarine, a complete fabrication for an animal that only grows to a still impressive 23 feet, but they did spin off the idea into its own fake documentary that aired during Shark Week 2014. They even interview a Submarine attack survivor played by Katherine Crawford, an actress with a lower leg amputation. The research team goes about trying to find the legendary shark, but then a shark spotter sees a whale getting attacked by something much bigger than Submarine. Next, Nazis. I'm not joking, the marine biologist uncovers a photo of a U-boat with a large fin sticking out of the water, showing an animal possibly 60 feet long. He assumes it is the exact same animal, patrolling the waters for over 70 years. After showing a poorly done CGI Hawaiian home movie of a whale with it's tail bitten off, they introduce the idea that this shark may be Megalodon, which they immediately refer to as "the serial killer of the sea" and saying it would eat "anything and everything in its path with extreme prejudice." They also grossly misrepresent the size of Megalodon, saying it could have grown to 100 feet even though the one they're tracking they estimate at 70 feet, which is still too big from what we actually know about the Megalodon. They talk about how it lacked compassion, as though that's something we expect from predators towards their prey; as well as exactly what color it was, something we have no way of knowing from fossils of teeth and vertebra. To further support their claim they refer to a Megalodon tooth found in 10,000 year old sediment, much younger than when scientists say the animal went extinct. The show undermines paleontology by saying their are only "unproven theories" about Megalodon’s extinction, as if it would be possible to definitively prove something from the deep past in they way they suggest would be necessary to verify the animal's extinction. When asked why the animal would suddenly and publicly reappear now? The answer is climate change. Warm up the oceans, it becomes easier for the shark to come back to it's old stomping ground to eat whales. What it was doing in the intervening 2.6 million years is left unsaid. Eventually the skeptical scientist character is convinced by Collin and the hunt is on to find the shark. They build a full-scale whale decoy and plan to dump 5,000 gallons of chum into the water. The show finally reaches a climax when the Megalodon shows up, at night, prompting the divers to hop in a shark cage to tag the animal while taking some blurry shaky cam footage from inside the cage in the now somehow chum-free sea before the cage disappears under the waves. Both divers escape the cage, with the camera no less and the now-tagged shark immediately dives to 6,522 feet out of the range of their tracker. "I believe we just encountered Megalodon." concludes Colin the biologist a moment before the disclaimer pops up on the screen. The caveat went by so quickly that I had to pause the show to be able to read it. For one second each the lower third of the screen shows the following statements:

Needless to say, none of the events depicted actually occurred. Snopes.com even published an article attempting to debunk the cavalcade of nonsense presented by the show and even cryptozoologists who maintain the possibility of C. megalodon’s continued existence were offended by the poor quality and representation of their field in the obvious attempt at higher ratings in lieu of accurate science. It would take much longer than a single episode of Skeptoid to go point-by-point through the blatant, egregious, and purposeful errors from he dramatized program. Rather, I'll touch on a few of the points related directly to the extinction of C. megalodon, and explain what actual science has to say on the matter. So what evidence do we have the C. megalodon is really extinct? It may sound a bit obvious, but at a certain point in the geologic record, around 2.6 million years ago, the fossils simply stop. The Discovery Channel show mentions teeth found in Pleistocene sediments dated to only 10,000 years ago but most scientists agree that this is an example of reworking, where a tooth erodes out of it's original rock, and then is re-preserved in newer rock. It's the same reason we occasionally find dinosaurs fossils just above the K-Pg boundary. One weird quirk of paleontology that everyone acknowledges that the first and last occurrence of a fossil are not likely to be the actual first and last appearance of said organism. However, using the best available methods, researchers still conclude that C. megalodon went extinct around 2.6 million years ago, which may sound like a precise date but on human timescales is actually a broad number. This date coincides with the rise of our modern composition of whale diversity, including the gigantic filter feeders like the blue whale, which were smaller in general during the time of C. megalodon. This is also around the time we start seeing orca in the fossil record, suggesting that there may have been intense competition driving C. megalodon to extinction or that orca evolved shortly after the extinction of the shark to fill that particular niche in the ecosystem, a role they still hold today. Some people might wonder why it matters if someone wants to entertain the fantasy of a monster shark lurking in the depths of our oceans. The problem is that this kind of thinking perpetuates an image of sharks as dangerous killers to be feared and disliked. While there are certainly some scary sharks out there, this is a huge misrepresentation of the group as a whole. Of the more than 470 species of shark, only a dozen or so (~2.5%) could be considered dangerous to humans, and of those dozen only three (great whites harks, tiger sharks, and bull sharks) have fatal attacks on humans in the double digits. These statistics are for what are considered "unprovoked attacks" where the human has not antagonized the animal, but is merely mistaken for food. The fact of the matter is that for the majority of shark species, a human in the water doesn't look anything like their normal food, and will simply be ignored or avoided. If anything, sharks have much much more to fear from us. While about a dozen people are killed by sharks each year (although recent estimates looking at just 2006-2010 bring that number down to four) we humans are responsible for killing over 11,000 sharks per hour resulting in an estimated 100 million sharks killed each year. Most of these kills come in the form of 'finning' wherein the shark is caught, their dorsal fin is cut off, and the still living animal is tossed back into the ocean where it will have zero chance of survival. The fins are then used in shark-fin soup. I would argue that one of the main reasons less is done to combat this cruel and unsustainable practice is that public perception of sharks, in part fueled by Discovery Channel's docufiction where they are literally called “serial killers”, maintains that sharks are somehow bad or evil, instead of just predatory animals trying to survive in an increasingly polluted and overfished natural habitat. Sharks are no more or less evil than any other of the myriad forms of life to evolve on this planet, and instead of fear-mongering about sharks no longer with us, I think we should be celebrating the amazing diversity of modern sharks alive in our oceans today. Ultimately, it's a shame that an organization that began as such a great promoter of science to the general public has strayed so laughably far from their original goal. If there's one lesson that we can take away from fictional documentaries like Megalodon: The Monster Shark Lives it's that if a program is purporting to teach the audience science, but uses audio and visuals to elicit fear and revulsion instead of awe and wonder, then you have very good reasons to be skeptical. By Ryan Haupt

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |