|

|

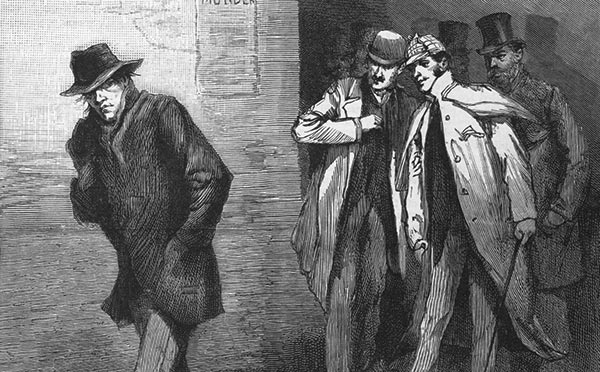

Catching Jack the RipperA look at what is and isn't known about history's most infamous serial killer. Skeptoid Podcast #304  by Brian Dunning Today we're going to pay a visit to London, specifically the Whitechapel district, back in 1888. It was a crowded, filthy, uncomfortable place, still stinging from the deadly Bloody Sunday riots of 1887 when Irish protesters clashed with police. Political unrest, unemployment, crime, rampant disease, and hunger were compounded with racial tensions between the Irish working class and Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe. Amid all this squalor, it's hardly surprising that violence and murder were common. In fact, those days and that place produced history's single most infamous murderer: Jack the Ripper. We're going to take a look at the common knowledge about Jack, and see how it compares to what's actually known and what's popularly believed. Who was he, how many did he kill, and how did we learn what we know? Poverty was so severe in Whitechapel — at the time, the acknowledged slum of London — that prostitution became one of the leading industries. It was a desperate move by a population, desperate from actual hunger and deprivation, to bring money into the community from London's wealthier West End. This workforce of an estimated 1200 women commuted every day and night on foot through unlit alleys filled with drunken factory workers and as many as 3000 homeless people in this neighborhood alone, and their victimization was all too commonplace. Police grouped eleven murders of prostitutes, committed between 1888 and 1891 and all apparently related in some way, and referred to them as the Whitechapel Murders. At the time, the presumed killer was known to the press as Leather Apron. Later, investigators separated five of the Whitechapel Murders away from the rest, believing them to be the work of a single distinct individual. The modus operandi was the same: the victims were first silenced and killed by strangulation, their throats were cut, and their bodies mutilated in similar ways, to varying degrees depending on how private was the location and how much time the killer probably had. Today, nearly a century and a half later, Jack the Ripper still grips the public's attention. Practically every year, a number of books and documentaries are produced naming some new suspect or claiming a fresh analysis on some piece of evidence. Please don't email me about this new book or that new book and its particular claims and its evident authority; the Library of Congress currently lists at least 181 different books with Jack the Ripper in the title; every one I've looked at introduces yet another suspect, and they can't all be right. Many believe he was an aristocrat or educated man from the West End, and some believe he was no more than a local thug. Today's enthusiasts and armchair investigators call themselves Ripperologists. The Ripper was never seen or heard and left no evidence that survives today, with the possible exception of letters received by investigators and newspapers claiming to be from him, and it's the signature of one of these letters that is the first recorded appearance of the nickname Jack the Ripper. But at the time, eyewitness reports abounded. Nine days after the Ripper's victim Mary Ann Nicholl was killed, Lloyd's Weekly London Newspaper published a detailed account of the presumed murderer, a local creep who seemed to be quite well known:

Whoever Leather Apron was, he may or may not have been Jack the Ripper and may or may not have been responsibile for some of the other six Whitechapel Murders. Today's criminologists and Ripperologists usually absolve Leather Apron of being the Ripper, due to the differences in style. Leather Apron swaggered around the streets making public threats, while the Ripper displayed a deep and very subtle pathology. It is the study of his evident psychosis that has driven Ripperology. Part of this was a particular obsession with excising the kidneys and the uterus. It's often reported that Jack the Ripper must have been a doctor, due to the presumed need for medical knowledge in order to mutilate his victims. In fact this suggestion has very little support. Dr. Thomas Bond, one of several experts brought in by the police to examine the victims to gain insight into the killer, made the opposite suggestion, that the Ripper did not have medical knowledge:

This was echoed by the murderer himself in one of his taunting letters mailed to investigators (September 25, 1888):

Indeed his behavior was most un-doctorlike; as he also wrote in a letter the following month addressed "From hell" and accompanying a small parcel containing half of a human kidney preserved in a tiny bottle of spirits:

Over the years, it's been suggested many times that a lot of Englishmen of the day had been involved in military campaigns in India and Africa. Various cultural traditions among certain Zulus and Indians would have become well known to British soldiers, including corpse mutilation. While this is intriguing, I found virtually no similarities between reported Zulu rituals and the things that the Ripper did. If the Ripper had been a soldier serving overseas at some point, I don't find that it had much to do with his murders. In 1975, the International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine published an interesting article that suggested the Ripper may have been medically traumatized as a child. The author surveyed the literature and found:

It's perhaps not entirely coincidental that the London stage adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, presented by the American actor Richard Mansfield, opened at the Lyceum theater on August 6, 1888, just three and a half weeks before the first of the Ripper's five murders. As the Ripper killed, the violent play ran to increasing public protest, depicting a man who transformed into a bloody killer. The play closed in late September, ostensibly due to negative publicity surrounding the Ripper's murders, and the proceeds from the final performance were donated to Whitechapel charities. Whether the stage play may have inspired or even triggered the murderer is a possibility that, unfortunately, leads us nowhere. Maybe it did, maybe it didn't; the Ripper left us no evidence with which we might bolster speculation. Leaving us with even less good evidence is the fact that the authenticity of all the Ripper's letters has been questioned. Handwriting analysts disagree on whether or not they match. Only one of the letters contains any information that would have been known to just a few people besides the real killer, and that's a letter written and received the same day that two of the five murders committed on the same night were discovered, and it boasts of them. But, the letter contains nothing that helps us learn the Ripper's identity. Beyond the few popularly reprinted letters were a grand total of over six hundred letters from "Jack the Ripper" received by various police and press agencies, and a number of people were actually arrested for writing hoax letters. Even the box with the kidney is shrouded in too much doubt to be certifiably authentic. As pointed out in 2008 in the Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation journal:

The bottom line is that there is no widely accepted evidence suggesting an identity for Jack the Ripper. There are many hoaxed diaries, claims of royal conspiracies, Freemason plots, and all sorts of theories that are all either disproven or based on pure speculation. This lack of evidence is not surprising, for as the editors of the Casebook: Jack the Ripper website ably summarize:

When you hear anyone claim to have finally solved the case of Jack the Ripper, you have very good reason to be skeptical.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |