|

|

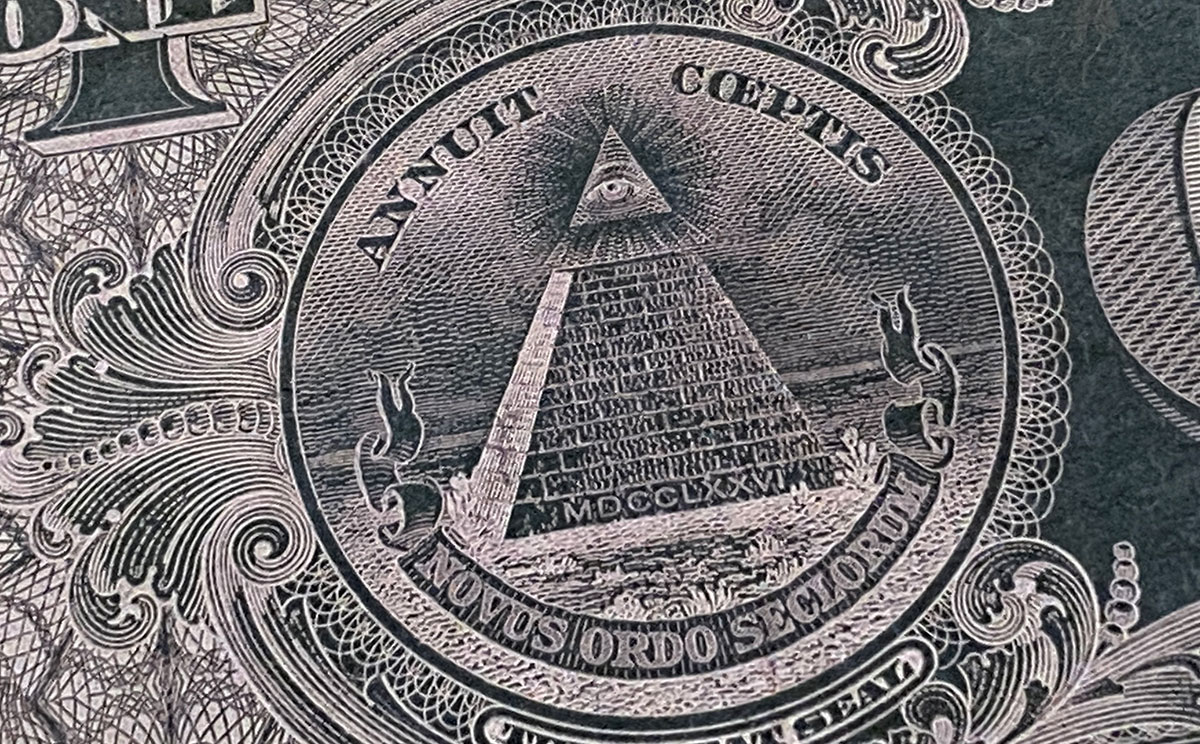

Conspiracy Theorists Aren't CrazyWe usually dismiss conspiracy theorists as crazy people; but that doesn't tell the whole story. Skeptoid Podcast #264  by Brian Dunning Today we're going to descend into the darkest depths of the human mind to learn what makes a conspiracy theorist tick; or, as some would put it, to learn why his tick seems just a bit off. Is there anything we can learn from the conspiratorial mind, and is there a method to its apparent madness? The human brain evolved in such a way as to keep itself alive to the best of its ability. For the past few million years, our ancestors faced a relatively straightforward daily life. Their job was simply to stay alive. Like us, they had different personalities, different aptitudes, different attitudes. This was borne out in many ways, but the classic example that's often used is that something would rustle in the tall grass. Some of our ancestors weren't too concerned, and figured it was merely the wind; but others were more cautious, suspected a panther, and jumped for the nearest tree. Over the eons, and hundreds of thousands of generations, the nonchalant ancestors were wrong (and got eaten) just often enough that eventually, more survivors were those who tended toward caution, and even paranoia. In evolution, it pays to err on the side of caution. The brains most likely to survive were those who saw a panther in every breath of wind, an angry god in every storm cloud, a malevolent purpose in every piece of random noise. We are alive today as a race, in part, because our brains piece random events together into a pattern that adds up to a threat that may or may not be real. As a result, we are afraid of the dark even though there's rarely a monster; thunder frightens us even though lightning is scarcely a credible threat; and we perceive the menace of malevolent conspiracies in the acts of others, despite the individual unlikelihood of any one given example. Conspiratorial thinking is not a brain malfunction. It's our brain working properly, and doing exactly what it evolved to do. So then, why aren't we all conspiracy theorists? Why don't we all see conspiracies all day long? It's because we also have an intellect, and enough experience with living in our world that we are usually able to correctly analyze the facts and fit them into the way we have learned things really work. It is, exactly as it sounds, a competition between two forces in our head. One is the native, instinctive impulse to see everything as a threat, and the other is our rational, conscious thought that takes that input and judges it. Let's look at two examples that illustrate the ends of the spectrum. David Icke is a British conspiracy theorist best known for his claim that most world leaders are actually reptilian aliens wearing electronic disguises. When you pause a video, he points to the compression artifacting and asserts that it's a glitch in the electronic disguise. However, he's out in the world, he tours, he writes books, he has a family and is a member of his community. He's not locked in an asylum as we might expect from hearing his theory. The reason is that he's probably not mentally ill at all. His brain is doing exactly what it's supposed to. He sees a group of powerful men, and the instinctive part of his brain suggests a sinister purpose. Imagine yourself seeing the ministers of the G8, or some similar collection. A thought passes through all of our minds, something like this: "I bet they all know something I don't know. I'd love to hear what they were talking about. They're up to something." That's the same thing David Icke thinks. It's exactly what our brains evolved to do. Our brains all want to go there. And then the intellect receives this warning, and analyzes it, based on its knowledge. We all have different knowledge built from different experiences. One who has had negative experiences with authority is likely to gauge this situation differently than one who has not. David Icke probably has some past experience that makes his intellect properly — if incorrectly — assign more credence to the threat than is necessary; overtly so, in his particular case. Most of the rest of us have rarely seen a news story where a secret collusion among world leaders was discovered, so our intellectual understanding of the world has good reason to reject this particular instinctive threat as being improbable. Thus we conclude that it's probably just a group of businesspeople doing what they have to do. We all fall somewhere along that spectrum, and all perspectives are the result of our brains properly doing their job. Take another example, this time of the Big Pharma conspiracy. Our brains see a group of huge, profitable companies in the same industry, and the pattern is obvious. Instinct throws up its warning flag. They're up to something evil, they are a threat. That is the brain's normal and expected first response. Next comes the intellectual filter to evaluate the reality of the threat. Only this time, many more of us match the threat to things we've seen in the news. There are genuine conflicts of interest in the pharmaceutical industry. Sometimes the rules for getting drugs approved have been bent. Drugs have been taken off the market after initial findings of safety, many times. In fact, the average person on the street probably knows little about the pharmaceutical industry except for examples of such cases making it into the news. In this case, the knowledge that many people's intellect uses to drive its conspiracy filter is likely to give this one a score of "Plausible". Let's look at the results. Suspicion toward Big Pharma is fairly widespread, while suspicion of reptoid aliens controlling the world is quite limited. Most other conspiracies fall somewhere in between these two. Whether it's David Icke seeing reptoids or your coworkers and neighbors shunning government approved drugs, it's the same thought process, and it's the brain doing its job properly. Like a classroom of students who all honestly studied hard yet still got varying scores on the test, our brains are going to be right sometimes and wrong sometimes. But they're all following the proper steps to get there; conspiratorial thinking is not necessarily, by itself, indicative of psychiatric illness. To determine when a person is over the line and should be treated, psychiatrists often look closely at the context. Does the conspiratorial belief integrate harmlessly with this person's life, or does it dominate? Has it caused problems: loss of job, loss of spouse, loss of security, or caused sociopathic behavior? These are the types of things that differentiate a belief system from what we call an illness. A person who thinks Barack Obama's birth certificate is fake is not ill, but a person who obsesses over it to the point of driving away their friends and family could well be. The diagnosis is often delusional disorder. It must be a primary disorder, which means that it's not a symptom of some other condition the patient may have, it has to be the primary psychopathology. There are six types:

Such people could benefit from treatment, usually a combination of drug therapy and psychotherapy. However, as we've discussed before on Skeptoid, getting them to agree to treatment at all is often the primary barrier. They believe their delusion is real. They will present their evidence to prove it until the cows come home. It's often impossible to get them to consider the possibility that the reality of what they perceive might be due, in any degree, to psychopathology. But if you've had a conversation with a conspiracy theorist — and almost all of us have — you've met people who do not display symptoms of delusional disorder far more often than those who do. The ordinary conspiracy theorist is an intelligent, sane, and generally rational person. They are, in fact, unsettlingly less different from you than you may have thought. Not all detection of purposeful agency sees something evil. For example, we now know that the sun, moon, planets, stars, and constellations are simply other bodies floating through space and doing their thing, much as our Earth does. But early human cultures, who lacked better knowledge, suspected them to be purposeful entities that existed only to influence humankind on this one particular rock. This brain function that kept our species safe from threats also formed the basis for pagan religions, the great polytheistic European cultures, and astrology. Note that astrology still thrives today. Astrology is psychologically similar to conspiratorial thinking. Both represent the healthy brain's perception of purposeful agency in ordinary phenomena, but one sees danger while the other sees comfort. All of our brains naturally take us there, and it is only our learned intellect that reins us back. We're all hard wired to experience a deep-rooted excitement at the thought of opening a fortune cookie, though most of us have learned to put little stock in the fortune. And if handed today's horoscope, few can deny that their brain will go straight to their own zodiac sign to see what it says. There is no need to be embarrassed about doing either of these. It's one of the things your brain is supposed to do. So, embrace your inner conspiracy theorist. Learn to identify and understand your own conspiratorial thinking, and you'll be better prepared to comprehend the position of the next conspiracy theorist you talk with. When you dismiss someone as paranoid or crazy, remember: it might be you who's wrong.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |