|

|

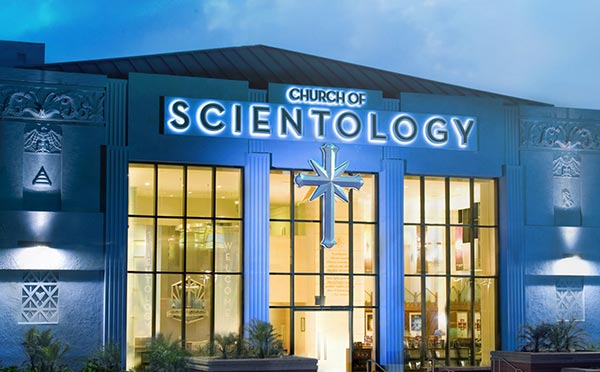

ScientologyThe real facts behind the most notorious religion on Earth and its space opera backstory. Skeptoid Podcast #242  by Brian Dunning Today we're going to point the skeptical eye at perhaps the most notorious of all the world's religions, Scientology. Many people laugh at it, some people hate it, some even dedicate their lives to protesting it. What is it about this twentieth century creation that inspires such emotions? Most people know the basics, that Scientology was invented by the science fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard, and that he drew upon his creativity to fashion a space-opera legend upon which it's based, featuring evil galactic emperors, space battles, explosions, and reincarnated beings. Most know that they do some interview thing with a kind of electronic lie detector, and that they shrewdly recruit celebrities to increase their public profile. But how does the public perception compare to the reality of the Church of Scientology and its mysterious founder Lafayette Ronald Hubbard? Hubbard grew up as a Navy brat, living wherever his dad was stationed, which was Guam in the late 1920s. In later life, Hubbard claimed that this somehow included being taught great wisdom by Chinese and Tibetan holy men, even being ordained by high priests; however no serious biographers or actual acquaintances ever took these stories seriously. As a boy he even claimed to have been made a blood brother of the Blackfeet Indians, for no clear reason. In other words, give an imaginative fiction writer a pen and who knows what you'll end up with. He spent his twenties having a singularly undistinguished college experience, never achieving decent grades or a degree, in part because he spent so much time writing. Hubbard was not merely a prolific science fiction writer, he was outrageously so. The 2006 Guinness Book of World Records named him the most published and most translated author of all time, with 1,084 works translated into 71 languages. The vast majority of those were fiction that had nothing to do with Scientology. Whatever you may think of the quality of his writing — truly objective opinions are hard to come by with such a notorious author — it's hard to deny that the man put eyeballs on pages. But despite his prodigious output, professional success as a writer did not come easily or soon, and the Navy ended up being his day job. By World War II he was a lieutenant in command of an anti-submarine ship off the U.S. west coast. As with so many aspects of his life, he greatly magnified his wartime career in his writings, and these exaggerations are still maintained by Scientology official records. They include his being injured in combat multiple times, having been the first casualty of the Pacific Theater, that he served in "all five theaters", that he received 21 medals and palms, and that he was a war hero who was twice declared dead. In fact he was never injured in combat, but only had pink-eye, bursitis, and an ulcer; he was relieved of the few commands he ever had for poor performance; and received only four medals, all four of which were given to every serviceman in the entire military stationed in the same theaters as he. Again, give an imaginative fiction writer a pen... After the war was when Hubbard's future finally began to take shape. He spent a lot of time in the Los Angeles underground occult scene, living for a while in a sort of devil-worshipping commune with JPL founder John Parsons. This was a place where the dregs of the Hollywood elite hung out, experimenting with hallucinogenic drugs and hedonism. Much of these crazy times is documented in the Parsons biographies Strange Angel and Sex and Rockets. It was said that the women in the commune found Hubbard irresistible, and he went through them one by one, not necessarily ingratiating himself with all the guys. It was during these bizarre days that Hubbard openly began telling his friends that starting a religion was the way to make real money, and when he first began outlining his plans. It began with Dianetics in 1950. Dianetics appeared simultaneously as the book Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health and as a chain of foundations around the United States to offer the treatments. Hubbard's basic idea of Dianetics is that negative experiences are stored in our minds as what he called engrams, and it's these engrams that are the source of all mental illnesses and other afflictions. He developed a process called auditing, where you are interviewed about your negative experiences by an auditor, until you no longer feel hampered by the engrams. The use of the E-meter, a simple galvanometer that Hubbard said should be held in the subject's hands, is alleged to allow the auditor to determine whether the subject has truly gotten over each engram. You are then what he called "clear" — free of engrams, and (supposedly) psychologically healthy. What Hubbard did was to simply take something that's fairly basic — the fact that talking openly about your problems and bad experiences is nearly always helpful — and pretended to have invented it, gilding it with his own terminology and accoutrements. I've no doubt that many people who undergo auditing find it a positive and empowering experience. But they could have gotten the same result from talking with a friend, counselor, or even a bartender. The formalized structure surrounding the auditing process is like a series of appointments with a therapist, ensuring that you'll complete the process; and the use of the E-meter makes it seem all the more dramatic and impressive. There's no evidence that auditing is useful by any recognized psychiatric standard, but that's a different question than whether the experience is personally fulfilling. Hubbard and his followers went to great lengths to try and get Dianetics established as a professionally recognized mental health regimen, but this was met instead with prosecutions for practicing medicine without a license, and bankruptcy. Unfazed, Hubbard then "saw the light", so to speak, and in 1952 he reframed Dianetics as a religion that he called Scientology. In order to present a quack psychological therapy as a religion, he needed a spiritual element; and so he drew upon his science fiction and created the idea of thetans. Thetans are immortal, incorporeal beings, who are reincarnated infinitely. We're each a thetan, you see, and before our thetans came to Earth we lived lives as alien beings on other planets, billions of years ago, accumulating engrams all the way. The history of the Church of Scientology since then has been an unending series of lawsuits surrounding its tax exempt status as a religious organization in various countries, the use of its E-meters as unapproved medical devices, trademark disputes, and just about anything else someone might sue someone else for. In the United States, Scientology's tax exempt status was the longest running and most expensive litigation in the Internal Revenue Service's history, and it was eventually decided in Scientology's favor. How do they pay for all these lawsuits? Well, they have a lot of money. Auditing is absurdly expensive, costing up to thousands of dollars; and each time a new member completes one series there is another even more expensive series to which they can graduate. Despite Scientology's claims of much higher membership, worldwide census estimates show there are probably around 50,000 people who identify as Scientologists. The vast majority of them are ordinary people like you and I, living normal lifestyles, who believe in the system and who pay for the sessions as they can. This aggregates into an enormous income stream for Scientology. The most dedicated individuals may choose to go full time, and this means joining the Sea Org. Originally founded aboard three ships by Hubbard, the Sea Org members mainly live on dry land now, living and working at centers in major cities and at Scientology's various "bases", where they do things like produce videos, learn to become auditors, manufacture E-meters, and preserve Hubbard's archives. Sea Org members are paid under the same tax laws as nuns and monks, which permits working hours for religious devotees far in excess of what labor laws normally allow, with minimal compensation. Their lifestyle is extremely structured. They wear uniforms, outside contact is prohibited or discouraged, daily routines are strictly regimented, and they are subject to all manner of surveillance and internal penal systems administered by higher ranking Sea Org members. Perhaps one of the best descriptions of the Scientologist lifestyle and its effect on members was revealed in Rolling Stone magazine in an article called Inside Scientology by Janet Reitman, later expanded into a book. Reitman investigated by three paths: She walked in the front door to their Hollywood campus and had the experience of an everyday new recruit; she phoned them professionally as a reporter and received a tour of their Gold Base in Hemet, CA; and she spoke with many current and former Scientologists. What she found were a number of disillusioned former members, and plenty of perfectly satisfied current members. Scientology is notorious for its litigious nature. Their lawsuits are usually directed at former members who speak out against the church. Members are required to sign contracts in which they agree never to do such a thing, so these lawsuits are rarely trivial. The reality of the threat of a lawsuit is very much part of the pressure that Sea Org members are faced with when they consider leaving. Ordinary members rarely have to worry about such things, but being in the Sea Org is an all-or-nothing proposition. It's often compared to being in the military. You sink or swim. The structured environment better work for you, because if it doesn't, you'll find yourself on thin ice. But such lawsuits are not the only reason that criticism of Scientology is justified. Their principal vehicle for attracting new income-generating members is a "free stress test" or "free personality test" offered out in the public, with no mention of Scientology, designed to be a quick, positive first experience with auditing. Then they draw you in with more such offers. As auditing purports to be a replacement for the sciences of psychology and psychiatry, Scientology often promotes a strong anti-psychiatry message, which is right up there with anti-vaccine quackery. While I certainly don't hold to any of the Scientology philosophy, and I think their science fiction thetan story with Lord Xenu is as ludicrous as anyone, I'm puzzled by the strong anti-Scientology passion expressed by its opponents such as the loosely organized group called Anonymous. I'm not Amish but I harbor no resentment to those who choose the Amish lifestyle, and I have no problem with people electing to dress in naval uniforms and live in regimented barracks. Whether Anonymous likes it or not, there are people who thrive in such a rigidly structured environment. It works for them, and it's as valid a lifestyle as any other. It's available for those who want it, and if you don't, nobody's trying to force it down your throat. There is no group of people in the world that's either completely perfect or completely evil. There are things about Scientology worthy of abhorrence, most notably their anti-science stance on psychology and psychiatry, and there are things about it that work great for those who choose that lifestyle. And so, although it may pain many of my regular listeners to hear it, Scientology is not on my list of the worst things in the world. Keep your skepticism healthy. [A followup to this episode is at https://skepticblog.org/ addressing much of the criticism. —BD]

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |